PEER REVIEWED

Meme factory cultures and content pivoting in Singapore and Malaysia during COVID-19

This paper is a qualitative ethnographic study of how a group of meme factories in Singapore and Malaysia have adapted their content programming and social media practices in light of COVID-19. It considers how they have fostered, countered, or challenged the rise and spread of misinformation in both countries. More crucially, the paper considers how meme factories position their contents to speak in a variety of platform-specific and age-appropriate vernaculars to provide public service messaging or social critique to their followers.

TOPICS

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- What are meme factories, how are they organized, and what is their role in the meme ecology?

- How do meme factories participate in socio-political discourse through their contents, in light of the rise of misinformation and related information suppression laws?

- How have meme factories pivoted their content and strategies in light of the COVID-19 pandemic?

ESSAY SUMMARY

- This paper considers how eight Singaporean and Malaysian meme factories serve as sentiment shapers that operate through the vernacular of visual internet pop culture.

- Meme factories are a coordinated network of creators or accounts who produce and host content that can be encoded with (sub)text and parsed into new contexts across multiple organizational structures.

- Meme factories often use strategic calculation to obtain virality or activate a call to arms to seed decision-swinging discourses, and at times with the potential to commercialize their meme contents for sponsors.

- From the qualitative empirical data drawn from personal interviews, digital ethnography, and content analyses of social media posts, the meme factories are found to mobilize four ways of addressing, challenging, and adapting to the influx of COVID-19 related (mis)information.

- In light of Malaysia’s (recently scrapped) Anti-Fake News Act and Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), meme factories are important for non-hegemonic views to be shared and seeded in constantly evolving and playful vernaculars that may slide under the authoritative radar through subversive frivolity.

Implications

This paper pivots from existing research on meme factories that have thus far focused on American-centric phenomena and online forums, to focus on instances of meme factories in Southeast Asia – specifically Singapore and Malaysia – and their occurrence on social media (e.g. Facebook, Instagram), messaging apps (e.g. Telegram, WhatsApp), and websites.

Existing academic literature on meme factories have highlighted that they can occur as online forums (Bogerts & Fielitz, 2019; Cohen & Kenny, 2020) such as Reddit (Donovan, 2019) and 4chan (Bernstein et al., 2011; Knuttila, 2011), meme-aggregator websites (Chen, 2012, p.13), and networks of actors such as Anonymous (Jarvis, 2014). Memes have also been studied as being “factoried” in the sense of being systematically produced en mass and milked for commercial value, although not all meme factories may be monetized. They have been brand-jacked and appropriated by brands and corporations (Milner, 2016, p.3), often resulting in an uneven reciprocity of gains (i.e. income) and losses (i.e. reputation) especially when “meme personalities” – “ordinary people can be (unwittingly) captured in compromising circumstances of with notable expressions or gestures and become ionized as memes” (Abidin, 2018a, p.44) – are involved.

Features & operations of meme factories

Through a triangulation of personal interviews, digital ethnography, and content analysis of posts published by meme factories in Singapore and Malaysia (see “Appendix” for detailed methods), I propose that meme factories are a coordinated network of creators or accounts who produce and host content that can be encoded with (sub)text and parsed into new contexts, often using strategic calculation to obtain virality or activate a call to arms to seed decision-swinging discourses, and at times with the potential to commercialize their meme contents for sponsors or monetize their labor. Specific to the sample in this paper, meme factories are sentiment shapers that usually operate through the vernacular of internet visual pop culture.

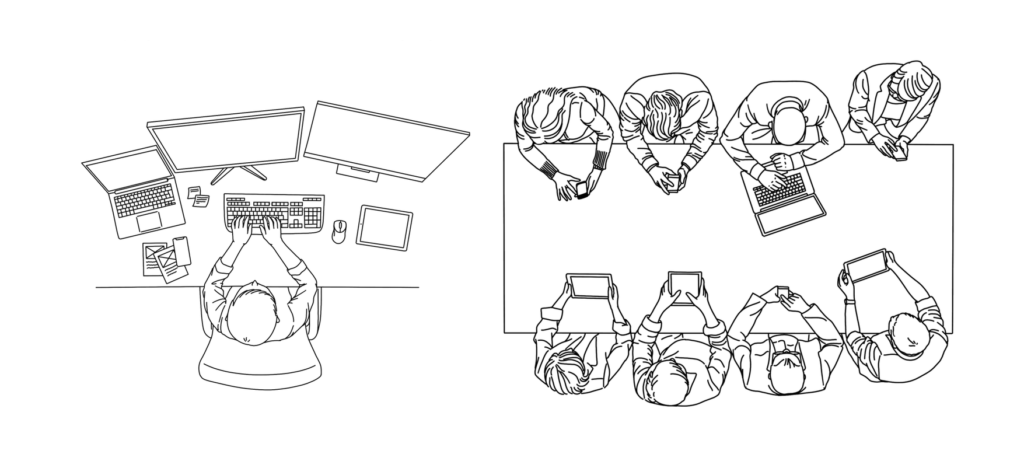

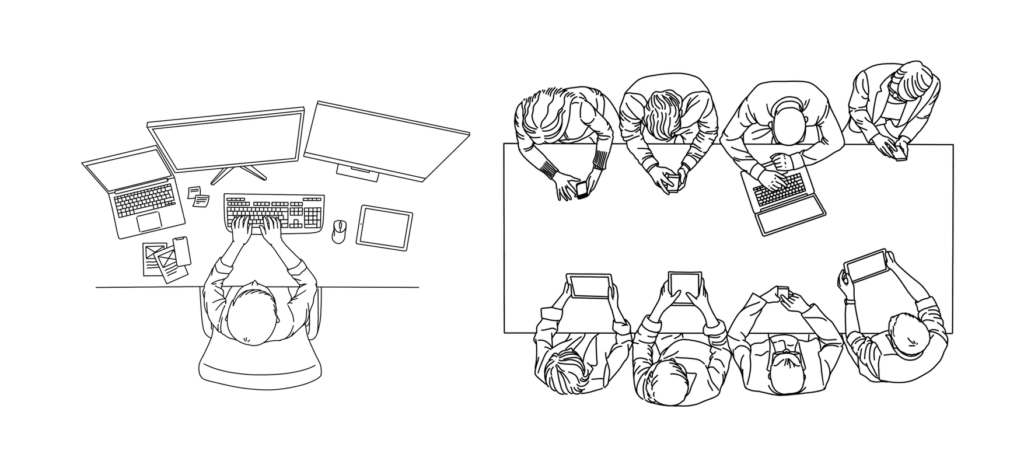

The meme factories studied in this paper are based in Singapore and Malaysia and founded between 2012 and 2018 (see Table 1). They operate on a variety of platforms including Facebook (pages), Instagram, Telegram, Twitter, websites, and YouTube. Meme factories can be a single creator managing a network of accounts and platforms (Figure 1) or a consolidated group of creators (Figure 2) who collaborate informally (i.e. hobby groups) or commercially (i.e. businesses). The ideation may result in contents that are strictly non-commercial, have the potential to be monetized, or are sponsored messages from the onset. Meme factories that operate across platforms may create bite-sized and long-form formats of the same contents, employ different aesthetics to convey the same message across platforms, or channel entirely compartmentalized messages on each platform.

FIGURE 2 (R): ARTIST IMPRESSION OF A CONSOLIDATED GROUP OF CREATORS AS A MEME FACTORY, PROVIDED BY AUTHOR.

Those catalogued in this study belong to three different modes of operations: Commercial meme factories whose core business is to create original meme content and incorporate advertising; Hobbyist niche meme factories that create or curate meme contents drawn on vernaculars and aesthetics to interest a specific target group; and Meme generator and aggregator chat groups who rely on volunteer members to collate, brainstorm, and seed meme content across other platforms.

COVID-19 content pivots

In light of COVID-19, meme factories have shifted to adopt four strategies: Firstly, some focus on producing entertainment by gauging and challenging the tonality of accepted humor in light of the rapidly progressing pandemic, and try to curb opportunistic bandwagoning; Secondly, some emphasize Public Service Announcements, adjusting between niche and mainstream references, by selectively surfacing, calling out, and amplifying specific issues for public awareness, prescribing behaviors, and shaping mindsets and discourse in the public arena; Thirdly, some pivot from meme production per se by considering alternative uses of their platform, serving as a sounding board for debate, reforming internal processes to increase the veracity of their source content; and lastly, some politicize their meme production by recentering the role of memes in the infodemic (access to required information obscured by excessive volume of competing (mis)information), challenging state censorship and authority, recalibrating new boundary lines, and calling out or catering to cross-generational consumption of memes.

Considering Malaysia’s (recently scrapped) Anti-Fake News Act (Al Jazeera, 2019) and Singapore’s POFMA (Bothwell, 2020) – which give the state an overarching authority to be the chief arbiters of the validity of information sources and to impose severe penalties to platforms, media outlets, and individuals for sharing non-sanctioned information, thus constituting a form of authoritative censorship – the role of meme factories in playfully mainstreaming marginalized discourses and subversively challenging the status quo through humorous internet vernacular cannot be understated. They are still the spaces where non-hegemonic views are allowed to survive, thrive, and even be celebrated. They are living archives of evolving vernacular strategies that can penetrate white noise and amplify messages to specific target groups in the age of misinformation. They are factories and vehicles of “subversive frivolity” (Abidin, 2016) that continue to slide under the authoritative radar.

Findings

In the sections below, this paper considers the three original modes of operation and four new pivoted content programming strategies employed by the surveyed meme factories in the time of COVID-19. It is found that the meme factories pivoted content to align with concerns and issues surrounding the pandemic. Their original strategies and new pivots during COVID-19 were determined by a triangulation of three sources of data: Personal interviews with key personnel in each meme factory, digital ethnographic data, and content analysis of specific memes published after the onset of COVID-19 in the Southeast Asian region (see Appendix for detailed methodology). The practices are not mutually exclusive, and while some meme factories draw from a range of strategies, they will be discussed for their dominant strategy at the time of fieldwork.

Meme factories’ original modes of operation

Finding 1a) Commercial meme factories run core businesses to create original meme content and incorporate advertising

MGAG, SGAG, and World of Buzz are commercial meme factories. MGAG and SGAG are sister companies belonging to Singaporean parent company HEPMIL Media Group, and produce videos and sell merchandise alongside their (commercial) meme-making. World of Buzz is one of several platforms owned by Malaysian company Influasia, and focuses on packaging news and current affairs into digestible and social media-friendly formats.

Finding 1b) Hobbyist niche meme factories create or curate meme contents drawn on vernaculars and aesthetics to interest a specific target group

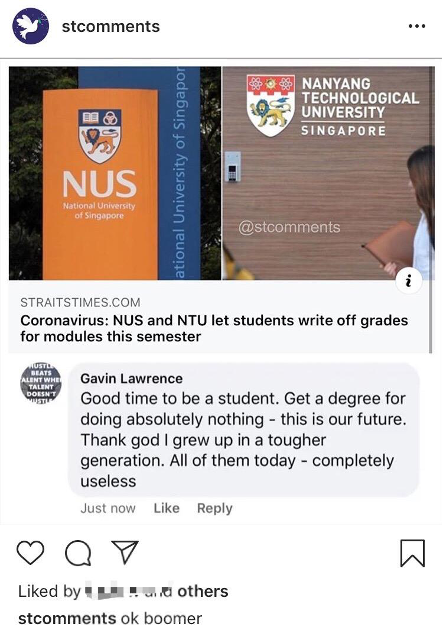

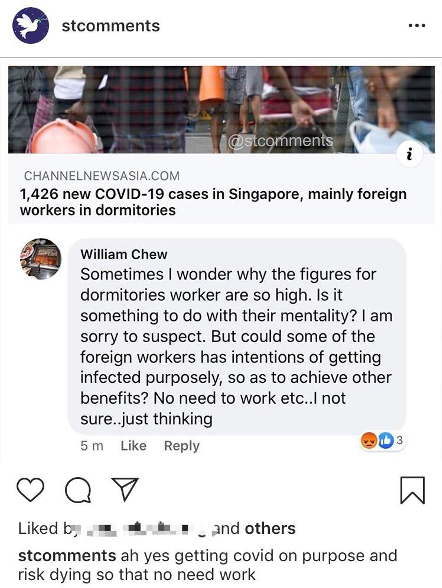

highnunchicken, Kiasu Memes For Singaporean Teens, STcomments, and Weiman Kow are hobbyist niche meme factories. highnunchicken and Weiman Kow produce original illustrations albeit in different styles and for different intentions. highnunchicken is a collective of four artists who produce sartorial takes on Singaporean life in the style of the New Yorker cartoons. Weiman Kow, is a hobbyist illustrator who started sharing her art on social media in 2017. Kiasu Memes For Singaporean Teens is run by a 28-year-old admin and founder who works professionally in the media industry and uses their platform as an avenue to share their creative spin on “hot topics”. STcomments is a Facebook and Instagram account managed by Ernest L who, after noticing “stupid” and “ridiculous” comments on the Facebook page of Singapore’s highest circulating English daily broadsheet The Straits Times, decided to collect screengrabs of these expressions.

Finding 1c) Meme generator and aggregator chat groups rely on volunteer members to collate, brainstorm, and seed meme content across other platforms

Memes n Dreams is a meme generator and aggregator chat group. It was first launched as a Telegram chat group in 2018, and at the time of the follow-up interview grew to over 21,000 members (“memebers”). The network is now spearheaded by 30-year-old Jackie Tan and two other admins (“admemes”).

Meme factories’ pivoted content programming

Finding 2a) COVID-19 Pivot: Memes as entertainment

General Manager Mia of MGAG recalls that when the Movement Control Order (MCO) (Tan, 2020) was first announced, her team decided that this was a “critical time to make content to uplift the spirits” of Malaysians, especially as they are among the most prolific social media content creation companies in the country and most people will now be spending extended periods of time online. One of their in-house talents is the character ‘Penang Guy’ who has the persona of a haughty and uncouth young man, and who complains about social issues in a mixture of colloquial Malaysian English and Hokkien; in light of the MCO, MGAG produced an episode of Penang Guy calling upon Malaysians to stay home through a series of humorously disgruntled complains (MGAG, 2020).

Likewise, CEO Karl of SGAG has directed his content production teams to focus on celebrating “heroes” and “heart-warming moments”. Prior to COVID-19, SGAG usually had focused content streams created in house and avoided reposting others’ contents too frequently. However, to “entertain the [wider variety] of people who are absolutely miserable at home” during the Circuit Breaker (Mohan, 2020), SGAG has expanded its content programming to accommodate audiences outside of their original target group. They now use their platform to reshare posts by other platforms and meme groups, as well as the “stories and content” that were created by others through the online activities and memetic challenges they have organized (Figure 3).

However, such commercial meme factories now face three tensions. Firstly, as media and advertising businesses that need to be sensitive to trending discourses online, they have had to accelerate their publication schedules. MGAG has shifted from publishing memes in six specific time slots to a rolling publication of unlimited content to immediately address or incorporate the latest COVID-19 updates in Malaysia. Mia calls this new routine “the timely meme”, in that her Creative Team are continuously on standby to create and publish original content as soon as there are new COVID-19 developments in Malaysia (Figure 4). An SGAG character Xiaoming also quickly responded to panic hoarding behaviour by staging viral photo-shoot with toilet paper as if a prized possession to lighten the mood (Ong, 2020).

FIGURE 4 (R): MEME REACTING TO THE EXTENSION OF MCO POSTED WITHIN MINUTES OF THE ANNOUNCEMENT, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM MGAG FACEBOOK PAGE.

Secondly, due to the rapidly shifting Out-of-Bound (OB) markers – topics censored by the state authorities and tacitly accepted and internalized by citizens, journalists, and other information providers (see George, 2012) – in-house moderation policies have to be constantly updated. MGAG’s COVID-19 meme guidelines include “non-biased” content that does not “bash [the] government”, criticize anyone, or promote negativity. To ensure that best practices are kept, MGAG’s in-house content moderator has stepped up to personally oversee and approve every meme at short notice before its launch. Similarly, SGAG has canned completed video productions before publication, and adjusted the script and subtext of their contents. Karl explains that they needed to stay “sensitive to the context of today’s climate and the situation at this point in time. It’s been a week-by-week adjustment as it gets more serious… [we are] being hyper-reactive to how we adjust our tonality.” The team has issued apologies and redacted content upon receiving vocal feedback, and the shelf lives of some memes have considerably shortened.

Thirdly, despite growing client demands to capitalize on the increasing online traffic, commercial meme factories have had to reconsider client requests that opportunistically capitalize on COVID-19. This is the practice of “grief hypejacking”, where users “bandwagon” on “high-visibility hashtags or public tributes” to direct publicity towards themselves or their own causes (Abidin, 2018b, p.170). Mia divulges that MGAG has had to “politely” reject some of the client requests that felt too self-promotional and exploitative of COVID-19. Karl echoes while some new clients were a natural fit for integrating COVID-19 messaging, such as insurance or internet data plans, others had to be “turn[ed] away”, likely because the clients did not understand the vernacular of meme ecologies at the current time: “our response [was] ‘No, please don’t do that, because it’s not the right time… to be talking about yourself right now as a brand’”.

Finding 2b) COVID-19 Pivot: Memes as public service announcements

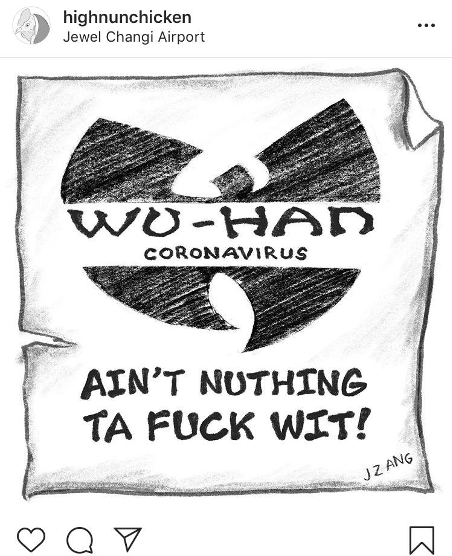

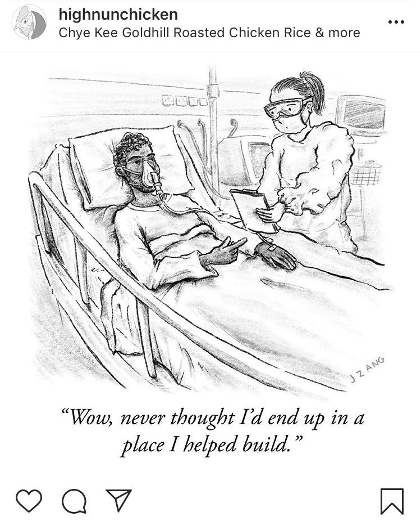

The contents by highnunchicken and Weiman Kow during COVID-19 have decidedly served as public service announcements. highnunchicken was one of the earliest meme factories to incorporate COVID-19 into their content stream, in a 22 January comic that remixed the Wu-Tang Clan logo into a ‘Wu-Han Coronavirus” poster (Figure 5). Illustrator JZ recalls: “when [the comic was published… there wasn’t a name given to the virus yet… [the phrase] ‘Wuhan Coronavirus’ was quite common when you did some research… [it was meant to be a] punny joke…” However, to his surprise, many of their viewers were not yet aware of the Coronavirus, let alone able to decipher the pop culture reference. When it soon became public knowledge that branding COVID-19 as a ‘Chinese virus’ incited rampant racism, the illustration collective decided to shift away from “sensitive topics” to focus on localized reactions to the situation in Singapore through strategic dark humor. Since then, highnunchicken comics have addressed panic buying, misinformation from elderly relatives (Figure 6), and the underreported poor living conditions of affected migrant workers (Figure 7), among others.

FIGURE 6 (R): MEME COMIC DEPICTING RELATIVES PEDALING UNVERIFIED HEALTH INFORMATION DURING CHINESE NEW YEAR, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM HIGHNUNCHICKEN INSTAGRAM PAGE.

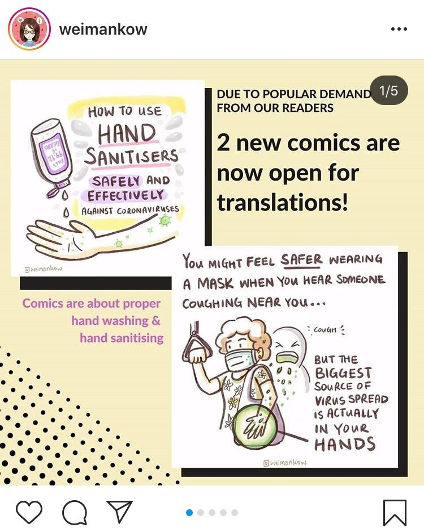

FIGURE 8 (R): ANNOUNCEMENT OF NEW COMICS OPEN FOR TRANSLATION, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM WEIMAN KOW INSTAGRAM PAGE.

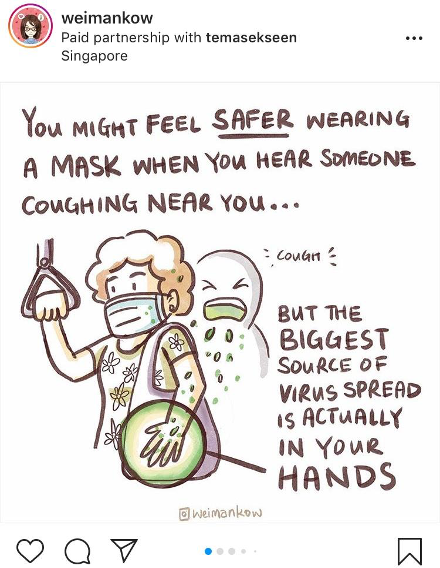

For hobbyist illustrator Weiman Kow, the directive is more straightforward, as she desires to clarify health-related misinformation and provide instructions for maintaining hygiene in an accessible format: “I believe that comics… that are based on facts are very useful to communicate… because they’re easy to understand”. Given her background in UX, Weiman draws on open sources cultures of collaboration, and makes her comics freely available in hopes that their transmission and translations will be able to better educate the public [Figure 8]. She has also been approached by prominent corporations who have commissioned to make more COVID-19 related comics to facilitate public learning about the correct information and procedures regarding hand washing (Figure 9) and hand-sanitizing (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10 (R): COMMISSIONED MEME COMIC DEPICTING EFFECTIVE HAND SANITIZING TECHNIQUES, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM WEIMAN KOW INSTAGRAM PAGE.

Above and beyond posting memes that are instructional or thought provoking, these meme factories also contribute to redirecting citizen attention to specific topics and amplifying particular discourses. highnunchicken’s coverage of COVID-19 usually calls out critical issues in the early stages of the information news cycle, before they develop into full-fledged national conversations. Their memes are important for publicizing ethical stances and shaping citizens’ thoughts as they are socialized into a national dialogue. JZ feels that highnunchicken’s role is to “throw out fire-starters” and provoke Singaporeans into reflecting on their behaviors: “We try to… address the whole situation in a funny way… call them out but also shine light on this issue to make everyone feel… self-aware”.

However, such memes may also be appropriated as misinformation against their creators’ wills. Weiman reports that some of her work was stolen by corporations, businesses, and brands who edited her comics into promotional content advertising health- and hygiene-related products. Others bandwagoned onto her growing microcelebrity by publicizing her memes alongside their brand name as if the artist had endorsed their products. At the time of writing, Weiman relies on the goodwill of the public to surface these instances to her.

Finding 2c) COVID-19 Pivot: New initiatives apart from meme production

STcomments and World of Buzz are meme factories whose regular content programming have incorporated COVID-19 related information, alongside a new pivot in their structure and/or processes to amplify specific types of information. The COVID-19 related posts from STcomments have called out citizens who have breached social distancing rules, citizens who are unsympathetic towards the adjustments to the education system in light of Home-Based Learning (Figure 11) and the rising xenophobia towards migrant workers in Singapore (Figure 12) These posts have sparked lengthy debates on STcomments’ Instagram and Facebook accounts wherein citizens affirm these call-outs, patiently negotiate with contrarians, or clarify misinformed takes on current affairs. STcomments thus serves as a platform for peer-education and peer-learning among citizens, and as a sounding board for negotiating the veracity of news sources and outlets against the backdrop of misconceptions. Similarly, World of Buzz has turned its content coverage to focus on COVID-19, covering ‘buzzworthy’ news stories including updates from the government, sacrifice of medical front liners especially during Ramadan (Figure 13) experiences of quarantine centers, and acts of charity (Figure 14).

FIGURE 12 (R): SCREENGRAB MEME CALLING OUT XENOPHOBIA AGAINST MIGRANT WORKERS, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM STCOMMENTS INSTAGRAM PAGE.

FIGURE 14 (R): LISTICLE MEME DESCRIBING ACTS OF CHARITY FROM MALAYSIANS DURING THE MCO, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM WORLD OF BUZZ INSTAGRAM PAGE.

However, both meme factories have also pivoted to new initiatives specifically to address COVID-19. On 4 April 2020, STcomments started a new content stream exclusively on Instagram Stories to provide “shoutouts for all local businesses/initiatives affected by the circuit breaker measures in my stories”. These shoutouts are compiled in a dedicated Instagram Story Highlight tab labelled “sgunited”, and promote small businesses including eateries, grocery delivery services, and job-seeking services, among others. Although other meme factories have monetised such advertising, this maintains a pro bono initiative by STcomments. Admin Ernest L explains: “[I’m] just trying to help out local businesses as much as we can. It isn’t much but I hope we’ve made some impact. Tough times for everyone and every little bit of help goes a long way.”

For World of Buzz which builds content for its website and Instagram page exclusively from news and social media stories, the pivot has focused on revised Standard Operation Procedures around fact-checking. The team has discovered that many reliable news outlets have published articles that extrapolated source material from non-robust outlets, or based entire news articles on speculation and rumor from internet forums. This is likely due to industry-wide pressures to publish COVID-19 related contents to retain audience interest and maintain ad revenue. The team is now training to assess and interpret primary sources such as industry and academic reports for health- and hygiene-related stories. Co-founder Michelle explains: “[We want] to ensure [that] no other publication will misinterpret [our articles], or mispresen[t] the studies [we have] dissected.” At the time of writing, Michelle is working with her employees to “reduce” the number of COVID-19 related reports they publish, to decentralize the hyper-focus on the virus and distribute reader attention across other stories.

Finding 2d) COVID-19 Pivot: Politicizing memes

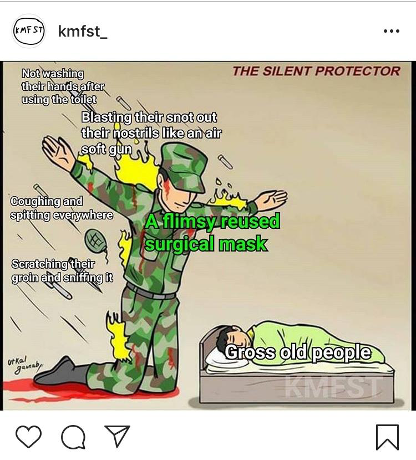

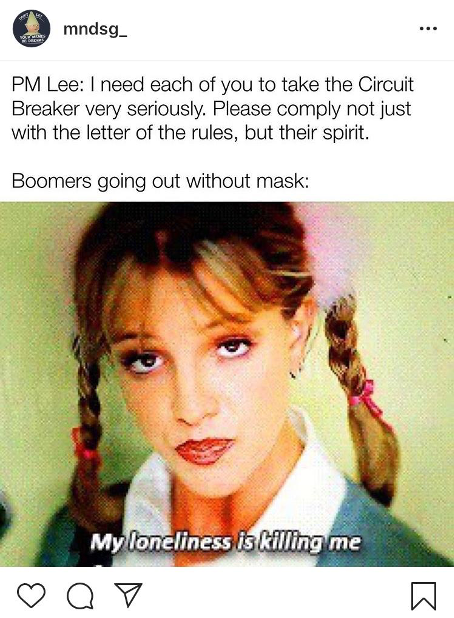

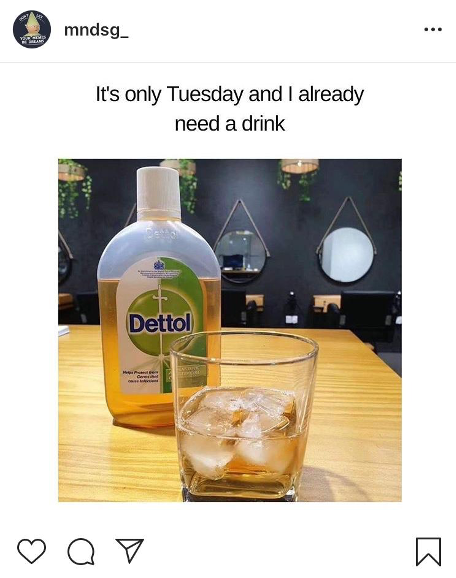

Admins of Kiasu Memes For Singaporean Teens and Memes n Dreams are using the COVID-19 infodemic to rethink the role of memes in the information ecology. The anonymous 28-year-old admin and founder of Kiasu Memes For Singaporean Teens offers that since he runs a “shit-posting site”, he is less concerned about fact-checking for his audiences whom he expects to be able to interpret cynicism and sarcasm. His recent memes have highlighted the exorbitant salaries of Ministers of Parliament in Singapore despite offering to take on pay cuts, inefficacy of Singapore’s COVID-19 contact tracing app, WhatsApp-based misinformation being circulated by boomers (Pang, 2020; Tandoc Jr & Mak, 2020) (Figure 15), and the false sense of security in donning masks when other basic hygiene practices are not kept (Figure 16).

FIGURE 16 (R): MEME CALLING OUT THE FALSE SENSE OF SECURITY ELDERLY PEOPLE HAVE WHEN DONNING MASKS, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM KIASU MEMES FOR SINGAPOREAN TEENS INSTAGRAM PAGE.

Admin Jackie Tan of Memes n Dreams who personally oversees and moderates the memes that circulate in his Telegram group observes that trending memes has shifted over time, and serve as markers of new normals during COVID-19: “I see [the trends] shifting from memes about the virus and where it comes from… more towards quarantine memes”. More critically, Jackie feels that “these virus memes [are] also a way to cope with the situation, reflecting “people’s current living situation[s] with social distancing [measures]” in place, such as the elderly feeling loneliness from self-isolation (Figure 17), and their ability to continue making jokes despite the circumstances (Figure 18). Memes n Dreams has a relatively relaxed moderation policy that only bans sexual and overtly commercial content. While there were a handful of racist COVID-19 memes posted to the group, Jackie recalls that members have not complained and thus no action has been taken. On reflection, he offers that perhaps such crass humour has been internalized by members as group culture, or that given the very high volume of daily posts, not so much attention was paid to racist memes in the long stream of continuous content.

FIGURE 18 (R): MEME DEPICTING COVID-19 HUMOUR BASED ON THE DEBUNKED RUMOUR THAT CLEANING PRODUCTS CAN HEAL INFECTIONS, REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM MEMES N DREAMS INSTAGRAM PAGE.

Both admins are reflexive about the role of their meme factories in the information ecology. The Kiasu Memes for Singaporean Teens admin desires to call out the onslaught of “rampant” misinformation and misinformed reactions he sees from “boomers” who comment on posts from the major English language news outlets in Singapore: “that’s their favourite activity… [to] spew whatever garbage that they can… [and] whenever someone online confronts them about how they are wrong, they just clam up, [or insist] that nobody [has] asked for your opinion, or nobody cares what you have to say”. One of his primary gripes is that censorship in Singapore, even of memes, seems imbalanced because none of the “boomers” spreading harmful content seem to be kept accountable. On the other hand, some meme factories have come under fire.

The admin explains that some of his fellow meme-making peers were “called down for questioning” under Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) (Singapore Statutes Online, 2019a) for creating memes deemed subversive or offensive by the state. However, undeterred by this, the admin felt challenged to be more experimental and boundary-pushing with his content stream: “[I want to] toe the line a bit, and kind of push the edge and see how much I can get away with”. He explains: “I’m not trying to get arrested… I’m always careful about religion and politics [in lieu of Singapore’s Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (Singapore Statutes Online, 2019b) and Sedition Act (Singapore Statutes Online, 2020)], but at the same time, it’s kind of the best content right? The most illegal things, the forbidden fruit…” He later reveals that the macro experiment of his meme factory is to test how “public sentiment” works in the information ecology in Singapore, and how only specific contents out of “a million other offensive posts” get “traction”, receive “public backlash”, and are escalated to “the Ministers’ eyes”.

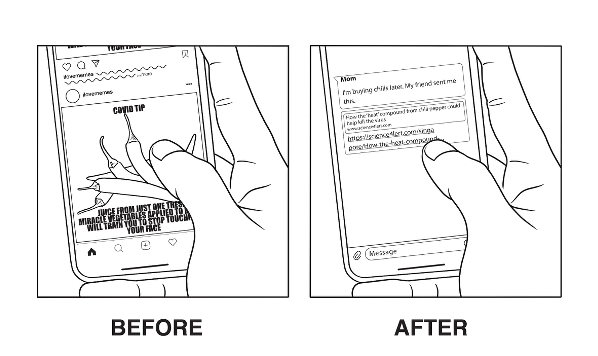

For Jackie of Memes n Dreams, the Telegram group has become a site for members to share misinformed memes shared by boomers on WhatsApp: “[Those] memes that are circulated amongst the older generation… end up in our group[chat] and we have a good laugh”. Here, WhatsApp-based and Telegram-based memes are perceived as antagonists, with the popular belief that the former are more accessible, spreadable, and lack fact-checking rigour. For instance, this author has observed how some memes that started out as satirical Instagram memes shared by the young quickly evolve into misinformed folklore and misinformation by the elderly on WhatsApp (Figure 19). Jackie points to the demographic of Telegram users who are generally younger and digitally literate enough to discern between memetic humour and misinformation. He offers that satirical or cynical memes that tend to contain “instructions”, or “prescribe some kind of behaviour” have the higher tendency to mutate outside of their context and become misinformation.

Drawing on his experience as a PhD Candidate in Biological Sciences, Jackie intends to take up the challenge of educating boomers with memes, by using memes like “vaccinations”, as a form of “thought contagion” (Lynch, 1996 in Linden et al., 2017). He explains that by intentionally “exposing” boomers to a certain set of memes, the spreadability of those memes will increase. With careful planning, there are ways to “inject memes” into the boomer meme ecology to “teach them about harmful memes”. Alongside the “harmful” memes that they are already constantly spreading, the new influx of healthy memes drawn from verified sources and prescribing robust information can also help “fight the harmful” ones among the elderly. This strategy might then break the cycles of “social reinforcement” in which “people who are more likely to trust an information someway consistent with their system of beliefs” (Bessi et al., 2015), by conditioning boomers to gradual exposure and acclimatisation. Jackie adds that this is an initiative he would like to formally institute should resources and time be available to him, considering that his work as an meme admin or ‘admeme’ is (still) a (non-remunerated) labour of love.

The role of meme factories, their ability to craft timely and sticky messages, and their potential to effectively seed sentiments among the citizenry is especially important in information ecologies where governments have a tight reign over information flows and censorship. Meme factories allow democratic citizen feedback, contentious opinions, and subversive challenges to filter through to the general populace through the highly mobile and palatable of memes. They are critical avenues for grassroots activism, and hotbeds for encouraging users to hone their media literacies through an timely news-gathering, intentional fact-checking efforts, politicised call-out cultures, and a careful navigation of the ever-changing OB markers of governments who control citizen discourse.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abidin, C. (2016). Aren’t these just young, rich women doing vain things online?: Influencer selfies as subversive frivolity. Social Media + Society, 2(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116641342

Abidin, C. (2018a). Internet celebrity: Understanding fame online. Emerald Publishing. https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/doi/10.1108/9781787560765

Abidin, C. (2018b). Young people and digital grief etiquette. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A Networked Self: Birth, Life, Death (pp. 160-174). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/A-Networked-Self-and-Birth-Life-Death/Papacharissi/p/book/9781315202129

Al Jazeera. (2019, October 10). Malaysia parliament scraps law criminalising fake news. Aljazeera.https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/malaysia-parliament-scraps-law-criminalising-fake-news-191010024414267.html

Bessi, A., Coletto, M., Davidescu, G. A., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2015). Science vs conspiracy: Collective narratives in the age of misinformation. PLoS ONE, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118093

Bothwell, E. (2020, April 6). Fake news law may ‘catch on’ during Coronavirus. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/fake-news-laws-may-catch-during-coronavirus#survey-answer

Chen, C. (2012). The creation and meaning of internet memes in 4chan: Popular internet culture in the age of online digital reproduction. Habitus, 3, 6-19. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.363.7029&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=6

Cohen, J., & K., Thomas. (2020.) Producing new and digital media: Your guide to savvy use of the web. Routledge.

Comics for Good. (2020, n.d.). Mission. Comics for Good. https://www.comicsforgood.com/about

Donovan, J. (2019, October 24). How memes got weaponized: A short history. MIT Technology Review.https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/10/24/132228/political-war-memes-disinformation/

George, C. (2012). Freedom from the press: Journalism and state power in Singapore. NUS Press.

Jarvis, J. L. (2014). Digital image politics: the networked rhetoric of Anonymous. Global Discourse: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Current Affairs, 4(2-3), 362-349. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bup/gd/2014/00000004/f0020002/art00022;jsessionid=8aj0kajbicpo0.x-ic-live-02

Knuttila, L. (2011). User unknown: 4chan, anonymity and contingency. First Monday, 16(10). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3665

Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., & Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global Challenges, 1(2). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/gch2.201600008

Lynch, A. (1996). Thought Contagion: How Belief Spreads through Society. Basic Books.

MGAG. (2020, March 27). Penang Guy asks you to #StayHome. Facebook.com.https://www.facebook.com/mymgag/videos/228430411724231/

Milner, R. M. (2016). The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. MIT Press.

Mohan, M. (2020, April 21). COVID-19 circuit breaker extended until Jun 1 as Singapore aims to bring down community cases ‘decisively’: PM Lee. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-circuit-breaker-extended-june-pm-lee-speech-apr-21-12662054

Ong, T. (2020, February 7). People all over S’pore clearing out supermarket shelves of food & toilet paper because DORSCON Orange. Mothership. https://mothership.sg/2020/02/panic-buying-supermarkets-sg/

Pang, N. (2020, March 31). How do we use messaging platforms such as WhatsApp appropriately in a crisis? Today Online. https://www.todayonline.com/commentary/how-use-messaging-platforms-whatsapp-covid-19-crisis-fake-news

Singapore Statutes Online. (2019a, April 1). Protection from online falsehoods and manipulation bill. Singapore Statutes Online. https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Bills-Supp/10-2019/Published/20190401?DocDate=20190401

Singapore Statutes Online. (2019b, September 2). Maintenance of religious harmony (amendment) bill. Singapore Statutes Online. https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Bills-Supp/25-2019/Published/20190902?DocDate=20190902

Singapore Statutes Online. (2020, April 28). Sedition act. Singapore Statutes Online. https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/SA1948?ProvIds=pr3-.

Tan, V. (2020, April 10). Malaysia’s movement control order further extended until Apr 28: PM Muhyiddin. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/malaysia-movement-control-order-extended-apr-28-12624310

Tandoc Jr, E. c., & Mak, W. W. (2020, April 27). Commentary: Forwarding a WhatsApp message on COVID-19 news? How to make sure you don’t spread misinformation. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/covid-19-coronavirus-forwarding-whatsapp-message-fake-news-12670016

FUNDING

Pre-COVID-19 portions of the fieldwork were funded by a Facebook Integrity Foundational Research Award (USA), January–December 2019.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ETHICS

The research protocol was approved by Human Research Ethics board at Curtin University, Ethics Office approval number HRE2019-0275.

COPYRIGHT

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are properly credited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to express gratitude to the meme factories, founders, and key representatives who have taken part in this study, especially for the entertainment, nuance, and subversion they bring to our internet worlds.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data for this study are protected by confidentiality agreements and we are precluded from sharing the data with others.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________